2. Human Rediscovery

Algae in historical legends

Microalgae have kept a low profile, but interaction with humans is notable on several occasions. The Bible describes when the Israelites were starving in the wilderness, God provided ‘manna’ – a flake-like thing, lying on the ground. They gathered the manna and baked it into bread. Some believe the manna was a kind of lichen – a combination of fungus and blue-green algae that formed a crust on the rocks and ground.

Another story took place a thousand years ago in Vietnam. A monk named Khong Minh Khong discovered rice was far more productive when a water fern, azolla, was planted in the paddies. The grateful farmers built temples to him after he died, but kept it secret.

Some 700 years later, a woman named Ba Heng rediscovered azolla. Growing rice with azolla continued for centuries, increasing yields and saving many people from starvation. Only this century did scientists discover blue-green algae living on the fern were fixing nitrogen as a natural biofertilizer for the rice.

Although freshwater or inland algae has not been eaten nearly as much as larger marine seaweeds, a survey of historical literature revealed at least 25 separate cases where 9 types of wild freshwater algae were collected and eaten in 15 countries. This non-seaweed algae has been used in a variety of soups, spreads and sauces and may have been an important source of vitamins and minerals.

When microscopic algae could be easily collected because it formed into larger colonies of mats or globules, it played a culinary and therapeutic role similar to many higher plants. So, eating algae may have been limited only by the difficulty of collecting these tiny organisms. Two cases, on separate continents, involved spirulina.

Rediscovery of the human use of spirulina

Dihé in Chad

In 1940, a little known journal published a report by French phycologist Dangeard on a material called dihé, eaten by the Kanembu people near Lake Chad. Dihé is hardened cakes of sun-dried blue-green algae collected from the shores of small ponds around Lake Chad. Dangeard also heard this same algae populated a number of lakes in the Rift Valley of East Africa, and was the main food for flamingos living around those lakes. The report went unnoticed.

Kanembu Spirulina Ladies harvesting spirulina from Lake Boudou Andja. Photos by Marzio Marzot from the FAO Report The Future is an Ancient Lake, 2004.

Two decades later, in 1964, the botanist with a Trans-Saharan expedition, Jean Léonard, noticed blue-green algae growing in the wadis (pools) that form to the northeast of Lake Chad after the rainy season. He then came across curious blue-green cakes in native markets of Fort Lamy (now Ndjemena) in Chad. When locals said these cakes came from areas near Lake Chad, Leonard recognized the connection between the algal blooms and dried cakes sold in the market. He observed that 70 percent of the food of the Kanembu was accompanied by a sauce made with these dried cakes.

Ladies harvesting and traditionally drying spirulina dihé in a sand filter. Photos by Marzio Marzot from the FAO Report The Future is an Ancient Lake, 2004.

Techniques of harvesting and drying have been passed from mother to daughter for generations. When the rains stop, Kanembu ladies scoop the wet algae in clay pots, drain the water through bags of cloth and spread out the algae a circular sand filter to dry in the sun. After about 20 minutes of drying, women cut the algae cakes into small squares for sale in the local market. Dihé is crumbled and mixed with a sauce of tomatoes and peppers, and poured over millet, beans, fish or meat.

Selling dihé in the local market. Locals use dihé sauce poured over millet. Photos by Marzio Marzot from the FAO Report The Future is an Ancient Lake, 2004.

In 2004 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported in the Kanem region of Chad, the local market price ranged from $.80 to $2 per kg – more than 10 times less than spirulina sold in developed countries. The average consumption of dihé could be as high as 50 grams per person per week. More than 250 dry tons per year is produced, making these ladies of Chad nearly the highest volume and certainly the lowest cost producer of spirulina in the world.

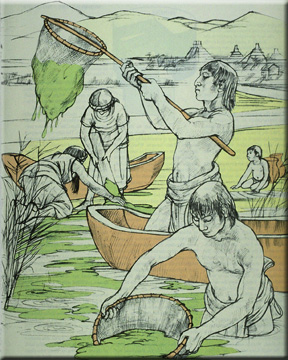

Aztecs harvesting blue-green algae from lakes in the valley of Mexico. Drawing in Human Nature, March 1978. (by Peter T. Furst).

Techuitlatl in Aztec Mexico

Around the same time in the 1960s, a company director in Mexico, Hubert Durand-Chastel, read about spirulina and realized it was the same algae clogging the soda extraction plant on Lake Texcoco. Although spirulina was not then eaten as a food in Mexico, an historical literature search revealed it had been harvested, dried and sold for human consumption 400 years earlier at the time of the Spanish conquest.

Spanish chroniclers described fisherman with fine nets collecting this blue colored ‘techuitlatl’ from the lagoons and making bread or cheese from it. Other legends say Aztec messenger runners took spirulina on their marathons. Techuitlatl was mentioned until the end of the 16th century, but not after that. Probably it disappeared soon after the Spanish conquest. The great lakes in the Valley of Mexico were drained to make way for the new civilization. The only remnant today, Lake Texcoco, still has a living algae culture.

Algae cultivation is an evolutionary step in agriculture

Over thousands of years, humans have increased food productivity at progressively greater environmental costs. Domesticating plants and animals encouraged the first permanent human settlements. About 7000 years ago, irrigation brought water to the land and food surpluses supported the first great river valley civilizations. Thousands of years later, when the land salted up from over-irrigation, these civilizations vanished.

A thousand years ago, the invention of an efficient plough in Europe allowed easier tilling of the soil. Europeans cut down the vast original forests bringing new areas under cultivation and new prosperity. The 19th century industrial revolution introduced mechanized agriculture, climaxing with the so-called ‘Green Revolution’ exported from the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.

Modern agriculture raised productivity with seed hybrids and massive fertilizer, pesticide, water and energy inputs. Productivity has been achieved by ignoring hidden costs, such as consumption of non-renewable fossil fuels for fertilizers and machinery, pollution of soil and water through use of chemical fertilizers and depletion of soils.

Successful algae cultivation requires a more ecological approach. A spirulina pond is a living culture and the whole system must be considered. If one factor changes, the entire pond environment changes – quickly. Because algae grows so fast, the result can be seen in hours or days, not seasons or years like in conventional agriculture.

Algae scientists talk of ‘balancing pond ecology’ for sustainable growth. Pesticides and herbicides would kill many microscopic life forms in a pond, so algae scientists have learned how to balance pond ecology to keep out weed algae and zooplankton algae eaters without using pesticides or herbicides. Algae cultivation is a new addition to ecological food production.

Scientists discovered spirulina had been safely consumed for hundreds of years by traditional peoples and showed nutritional and therapeutic health benefits. Spirulina had three great advantages over other microalgae: 1. Documented history of safe human consumption. 2. Grows well in warm, highly alkaline and high pH water, and in those conditions can grow as a pure culture. 3. With a long spiral shape filament, it is relatively easy to harvest.

A spirulina farm can be an environmentally sound green food machine. Cultivated in shallow ponds, biomass can double every 2 to 5 days. This productivity breakthrough yields over 20 times more protein than soybeans on the same area, 40 times corn and 400 times beef. Spirulina can flourish in ponds of brackish or alkaline water on already unfertile land. In this way, it can augment the food supply not by clearing the disappearing rainforests, but by cultivating the expanding deserts.

However, it hadn’t been done yet! No one had successfully cultivated spirulina on a large scale and convinced anyone they should indeed eat algae! If it was indeed an idea whose time had come, it was, nonetheless, a daunting task.

The first spirulina bioneers emerge around the world

In one of the first books on algae, “Spirulina, the Whole Food Revolution”, Larry Switzer wrote: “For the first time since the appearance of man, both wilderness and food productivity can be increased simultaneously with a new technology. This is a choice that man has never had before. The rediscovery of this ancient life as a human food has great implications for us all, now and in the 21st century. It is an example of the myriad of unexpected and astounding solutions to basic world problems that are now beginning to appear together on this planet.”

The San Francisco Examiner article in 1977 ”Just Close Your Eyes and Chew” introduced spirulina as “Food of the Future”.

A new planetary idea often incarnates through many messengers. This was true with spirulina. Hubert Durand-Chastel encouraged the soda ash company to set up a farm in Lake Texcoco in the 1970s, and it became the world’s largest spirulina farm by the 1980s. He became Senator of France and spirulina promoter.

Larry Switzer founded Proteus in 1976, and was joined by Robert Henrikson, Alan Jassby and Ronald Henson. This team began spirulina cultivation in California’s Imperial Valley in 1977. This pilot farm led to the founding of Earthrise Farms in 1981, which became the world’s largest spirulina farm by the 1990s.

Dainippon Ink & Chemicals (DIC) of Japan, established Siam Algae in Thailand in 1980. Former DIC Presidents, Shigekuni Kawamura and Takemitsu Takahashi, were long time spirulina sponsors. Heading the program was “Mr. Spirulina” in Japan, Hidenori Shimamatsu. DIC and Proteus formed Earthrise Farms in 1981.

In the early 1980s, Cyanotech began spirulina production in Hawaii and growers in Taiwan emerged. Israeli, Indian and European scientists conducted cultivation research. Others focused on village scale and appropriate technology farms, notably Dr. Ripley D. Fox and Dr. C.V. Sesahdri of India.

Spirulina began selling in Japan and Mexico as a health food and specialty fish feed in the late 1970s. In the USA it was introduced in 1979 through natural food stores and network marketing. By the early 1980s, marketing algae as a specialty food supplement was picking up momentum.

Why Spirulina? | 1. Original Lifeform | 2. Human Rediscovery | 3. Superfood Nutrition

4. Health Benefits | 5. Cultivation Worldwide | 6. Products and Markets | 7. Future of Spirulina

SPIRULINA

SPIRULINA